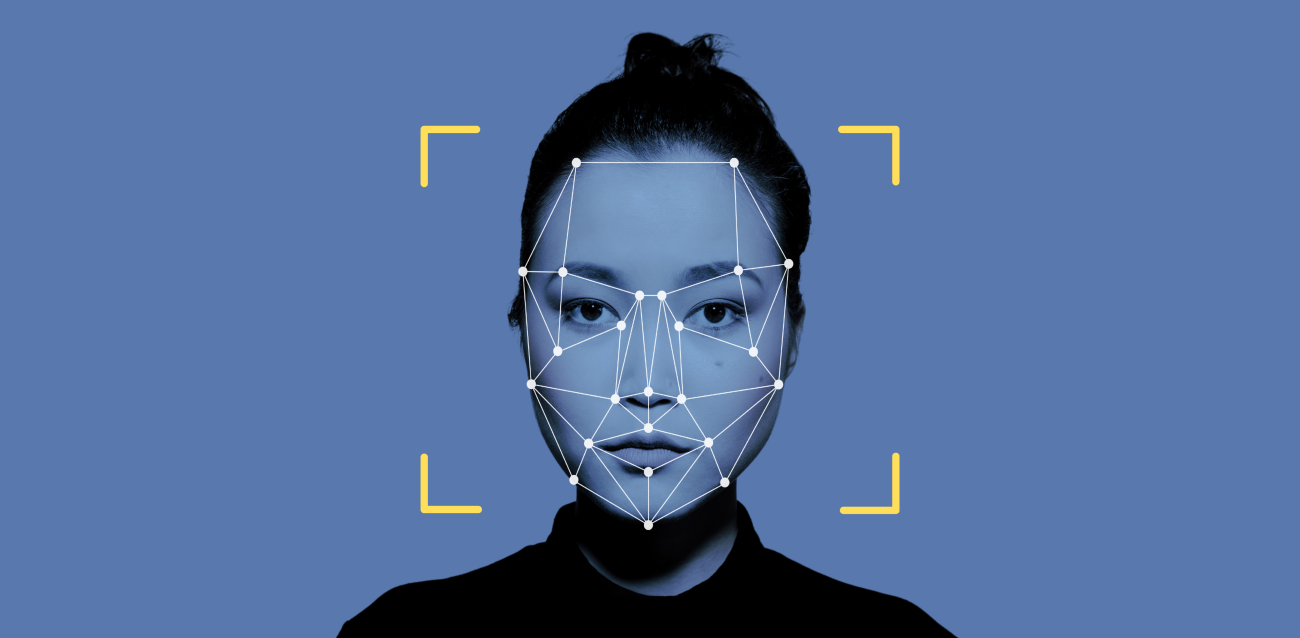

If you’re a regular user of the internet, the chances are you’ve come across a deepfake in your time, knowingly or not.

Deepfakes are a type of synthetic media, meaning images, audio and video that have been heavily manipulated by AI. Since their emergence, deepfakes have become increasingly common in online spaces. This is due to an overwhelming progression in the simplicity of the software needed to create a deepfake – anyone can download a face-swapping app to warp reality, causing a wrath of misinformation that is very difficult to separate from factual knowledge.

When they first hit mainstream media, deepfakes were often used for comical value. The concept was simple: replace someone’s face with another to add humour to a piece of digital content. They caught the attention of audiences, with one video on YouTube attracting 3.1 million views and 174,000 likes. But when created by the wrong hands, deepfakes are not comical. Misleading videos started popping up, with many high-profile personalities reduced to victims of propaganda – all because of one person and a smartphone.

But perhaps most alarming are the risks posed to women and children. Research has found that non-consensual deepfake pornography now accounts for 96% of all deepfake videos on the internet. Years of digital footprint built up by unassuming young women means it’s easy for a perpetrator to extract a face and apply it to sexually explicit images. We find it very concerning that digital footprints – a ubiquitous component of internet usage – can be manipulated to such extremes. Personal data might be ‘the new gold’, but its potential to do good is clouded by the people immorally mining it.

As with much media-influenced porn, deepfakes have a total lack of reality behind them. Not only are they completely non-consensual, but they are also likely to feature violence and degrading behaviour. It’s artificial intelligence at its worst, with perpetrators almost operating a ‘made to order’ online shop – bringing a fantasy to life at the expense of innocent women. While this may sound extreme, there is a harsh reality to it: as long as people have the correct technology, they can tailor pornography to their deepest desires, no matter how abusive or psychologically jarring. Perhaps audiences don’t feel as guilty if they know this is an ‘alternate reality’, and that, in their eyes, nobody is being ‘truly’ consumed for sexual gratification. As one man told the BBC, “They can just say, 'It's not me - this has been faked.' They should just recognise that and get on with their day.” Some argue that less harm is caused due to the recyclable nature of deepfakes; more videos can be produced from the same footage, so there's supposedly little incentive to exploit vulnerable people for new content. But this is a dangerous line to cross. People may flip the coin and say that deepfakes are creating a more ethical porn industry, but abuse has still occurred If the images used to create them are taken without consent.

VoiceBox have spoken before about the limitations of UK law, which requires proof of intent to cause harm before a person is prosecuted for sharing non-consensual imagery. Only in Scotland has this loophole been abolished. But even with the aforementioned milestone in Scottish legislation, we are still concerned for the victims of deepfakes, when, as another man told the BBC, “it's a fantasy, it's not real.” If someone wasn’t physically there when sexual abuse occurred, it may add yet another complexity to the ‘legal but harmful’ grey area that is currently sitting within the Online Safety Bill.

Three years since the Bill was first drafted, technology has moved at such a pace that proposed legislation has been unable to keep up. The UK wants to be the “safest place in the world to be online”, and yet deepfake software is readily available for anyone to exploit. It’s right there, sitting in our app stores, free to download and easy to use. Until certain applications of deepfake technology are legally recognised as harmful, the Online Safety Bill will not adequately protect children and young people.

Support Young Creators Like This One!

VoiceBox is a platform built to help young creators thrive. We believe that sharing thoughtful, high-quality content deserves pay even if your audience isn’t 100,000 strong.

But here's the thing: while you enjoy free content, our young contributors from all over the world are fairly compensated for their work. To keep this up, we need your help.

Will you join our community of supporters?

Your donation, no matter the size, makes a real difference. It allows us to:

- Compensate young creators for their work

- Maintain a safe, ad-free environment

- Continue providing high-quality, free content, including research reports and insights into youth issues

- Highlight youth voices and unique perspectives from cultures around the world

Your generosity fuels our mission! By supporting VoiceBox, you are directly supporting young people and showing that you value what they have to say.